The Washington Post, Washington, D.C.

OF DRIFTWOOD AND DIRGES

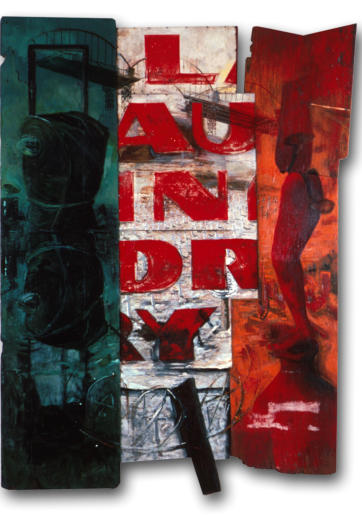

By Paul Richard May 30, 1990 Greg Hannan and Sabina Ott paint pictures that feel both new and Victorian. A strange funereal perfume -- of beeswax and mahogany, of forest glades and mists and withering floral wreaths -- scents "Memory, Time, and Recognition," their "Gallery One" exhibit at the Corcoran Gallery of Art. A solemn antique music -- of stirring ivy leaves and church bells damped by mist, the slap of waves on wooden hulls and the rustling of lace -- rises from their pictures. Their exhibition sighs. The sleekness of postmodern art - - with its wan appropriations, its disputations upon commerce, its chic reflections of the media -- is missing from this show. These artists paint laments. Washington's Greg Hannan, who rarely works on canvas, prefers to paint on weathered wood -- on bits of broken boats, or old and flaking signs, or peeling plywood sheets -- on surfaces already badly beaten up by time. Ott, who's from Los Angeles, does not employ found objects, but she too seeks a look suggesting layered time. Her elegies are painted on panels of mahogany, or on mahogany she's coated with photostated rose leaves. These are literary artists. Their sad and somber stories -- of loss and of remembrance -- lead us toward the past. Their past is not the past studied by historians, but something far more personal. Their works evoke the flow of memories retrieved while mourning for a loved one, or reading lyric poetry, or walking by the sea. Hannan's "Devil's Purse" (1988) is a plain, sign-simple image of one of those black egg sacks from a stingray or a skate that one finds on the beach. "Simultaneously an abstract icon and a descriptive rendering," writes the Corcoran's Terrie Sultan, who organized the show, " 'Devil's Purse' suggests hidden secrets partially revealed." Its bat-black image whispers death while its weathered plywood panel, rescued by the artist, hints at resurrection. That old and damaged plane of wood, washed with subtle grays, evokes the fogs that veil the sea. The life that follows death is a central theme of Hannan's art. His purple cloths suggest the shrouded statues of Roman Catholic churches. His swamps made bright by heaven's light, his winged hearts and crosses, his boats and broken bridges -- and the beauty he recovers from sheets of ruined wood - - sing a promise of salvation. Hannan's touch is richly varied, and his control of surfaces is almost always sure, but his imagery at times is just a bit too obvious. The coils of barbed wire in his "Irish Flag" (1986-87), its corpses and its crosses, are too- familiar, too-cartoony symbols of the Troubles of that land. His newer works are stronger because they're more mysterious. The tentlike forms appearing in the drawing on old wood that he calls "Disengage" (1989) suggest the shelters of the patriarchs, flaming towers in the desert, sproutings and tenacities and faith under attack. Religion plays a part in Hannan's metaphysics. His polyphonic dirges often sound like Christian hymns. The songs sung by Ott's paintings sound like love songs for the dead. The images recurring in her half of the exhibit -- a spray of fading roses, an ivy-covered wall, a veil gray as grief (or as red as dripping blood) -- suggest mementi mori. The ovals she employs -- sometimes they are cameos, sometimes wreaths of mourning, or tall Victorian mirrors -- conjure up the presence of a loved one lost. A weeping Queen Victoria -- all veiled in black lace, with pressed flowers in her prayer book and a cameo of Albert ever-present on her breast -- might have dreamed such dreams.

Queen Victoria and her subjects read allegories drawn from myth as

easily as road signs. Ott's scattered Xeroxed leaves, her layers of

poured colors and non-perspectival spaces would have baffled those

pre-modernists, but they would have had no trouble with her

mythological allusions.

The nearly abstract pictures that she describes as "portraits" of Echo

and Narcissus retell Ovid's story of the handsome youth and the

nymph he spurned. Narcissus, you'll remember, was condemned to fall

in love with his own reflection. Ott's tall oval portrait, fringed with

forest trees, suggests the face-reflecting pool on whose banks he

pined to death. Echo was condemned to repeat the last words she

had heard, and Ott's oval Echo portrait here suggests the nymph's

laments growing ever fainter as they vanish in the mists. Ott's often-

ghostly surfaces -- of oil paint on paper, mahogany and melted wax

-- are movingly evocative. Frequently she titles her past-retrieving

pictures "Disappearance and Return."

More than just a few contemporary painters seek art that's wholly

new, that's like nothing seen before. And just as many struggle to

reach back all the way to the prehistoric images of Stonehenge and

Lascaux. Ott, and Hannan too, while looking toward the past do not

reach back quite so far. Their closest allies are in some ways the

darkly symbol-conscious careful English painters of a century ago.

The "Gallery One" exhibits are a credit to the Corcoran. And all the

artists chosen for this series of small shows, including Ott and Hannan,

are now represented in the gallery's permanent collection.

article:

www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1990/05/30/of-

driftwood-and-dirges/

IRISH FLAG, 1987, acrylic on found wood and metal 98” x 72”