Arts & Entertainment : Art Review

Lost and Found

"Greg Hannan: Recent Work" By Glenn Dixon • April 11, 1997 At Numark to May 3 Most visual artists who don't harbor an inborn antipathy to language, even those who employ words in their work, still shun the title of "narrator." But Greg Hannan sees storytelling as his job, even if his means of spinning a yarn is rather oblique. What's more obvious is that Hannan is also a connoisseur of the found surface. Whether working in Shaw, where he lives, or in Westport, Nova Scotia, where he spends summers on Brier Island in the Bay of Fundy, Hannan keeps an eye out for evocative detritus. Possessed of a romantic sensibility, he favors distressed surfaces, but unlike many of his memory- obsessed contemporaries, he knows better than to fake it. He's willing to wait. Shaw Hull is a slender form, like the side view of a boat, consisting of two pieces of metal, one formerly part of a garage-door proscenium near Hannan's studio. Although he joined this find to another, then stretched the two over a wooden frame, it was its unaltered outline and natural weathering that suggested a hull stained by the sea. If it's somewhat perverse for Hannan to craft nautical works from landlocked refuse, Limbic Brain and Mirror is more curious still. A "self- portrait" on paper, it depicts the front and back of a Hummel figurine that Hannan found in Canada in "a burned-out pile of trash on the back of the island." Before he drew it, he stuck the ceramic knickknack in a piece of found marine putty and wove a brief narrative around it, describing a situation he likens to "the youthful sage ascending the mount with the book of knowledge, and he turns around and looks behind him—and he's standing in shit." (Hannan explains that the limbic brain is what governs, among other things, the fight-or-flight response, and that throughout his life he has more often than not disregarded its urgings, to his detriment.) Even more self-contained work, such as Island Heart/Head, comes with a story. A worn, cagelike, football-size construction on the end of a short pole, the piece incorporates a marine float, broken open to reveal its sullied, lunglike porousness, and part of the framework of an old lobster trap. But the bracket that holds the pole, painted turquoise in a marine paint common throughout Maine and the maritime provinces, was salvaged from a boat scuttled for insurance money. (As advanced technology leads to almost perfectly efficient fishing, the Canadian fishing industry is threatened by shrinking supply. Rather than go under or be legislated out of business, some fishermen opt to "blow" their boats, burning them at sea for the insurance money. Hannan says it's not an uncommon way to quit the business.) If Island Heart/Head can be read not only as a marker of personal desolation but as a requiem for a way of life, other pieces of Hannan's are more specific remembrances. "A lot of my work is about memoria, about people who have died in my life, many of them quite violently. And I don't know why I'm surrounded by this, but I am....The only premise that I've been able to reach through all this time is that the people that I've known that have come closest to God are dead," Hannan testifies. One of two stories surrounding the creation of Time to Get to Yellow #2 involves the "unexpected and very tragic" death of Hannan's "closest living friend's daughter." A painted-over window Hannan found in Shaw is butted up against an "abacus" made of small marine floats, Yellow is as much the result of serendipity as Hannan's hand. The yellows of the two sections just happened to match almost exactly, while a box Hannan shipped down from Canada coincidentally contained 77 floats, precisely the number required for the type of abacus the artist wanted to construct.

Such occurrences seem wrapped up with Hannan's thoughts of the

woman's possible "reincarnation," the prospect that "she would have

a chance again" to escape "the mistakes that she made that killed

her."

Hannan says that although he welcomes the attention they receive,

he's ambivalent about telling outright the stories that accompany his

pieces. "I feel handicapped in the present culture—glossing over,

and people picking things for their formal qualities," he laments,

pointing out that he's certain he would be criticized were he to

accompany each piece with a printed narrative.

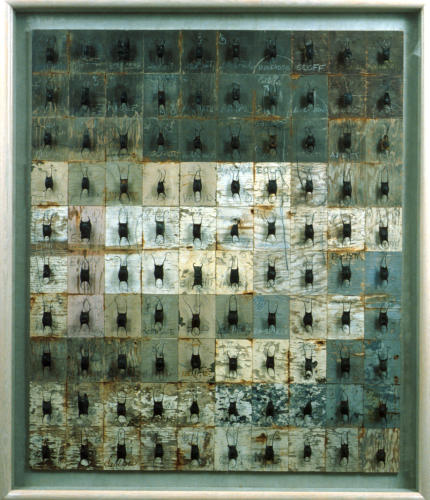

In the show's centerpiece, 100 Sins, Hannan has hit upon found

natural imagery that transcends his narrative of the piece's genesis in

a fated relationship. Arranged on a 10-by-10 grid of rectangles cut

from weathered wood are 100 "Devil's purses," skate egg sacs that

washed up on the beach. Each position is accompanied by a

scrawled "sin," a loose designation encompassing traits, actions, and

characteristics that make for human frailty.

It is not these words or the many Mars/Venus-male/female symbols

scrawled near them that govern one's perception and memory of the

piece, however, but the sacs themselves. Their bulging centers

emphasize their ominous pregnancy, while their tendrils evoke

vestigial limbs, perhaps splayed on a St. Andrew cross. As much

pillow as purse, the sacs' centers may represent a joining on a central

bed of two figures suggested by opposing pairs of tendrils.

They are menacing, fragile things. Washed with salt, their crevices

harboring grains of sand, their velvety black surfaces made to be

broken open, they imply, like Hannan's works, that they are vessels

for stories other than those that founded them, other than those we

choose to tell.

CP

Link to article:

www.washingtoncitypaper.com/lost-and-found

100 SINS, 1997, skate sacs, wood 50” x 42” x 6”